Background Data

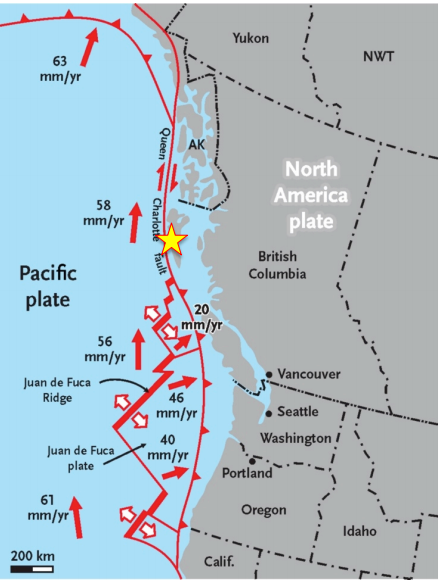

Just offshore of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, the North American Plate, the Explorer Plate and the Pacific Plate meet at the Explorer Triple Junction. It is at this point where the Cascadia subduction zone meets the Queen Charlotte-Fairweather Fault and the Juan de Fuca Ridge. (Rohr 1995)

“The Queen Charlotte-Fairweather Fault extends more than 1,200 kilometers (750 miles) from offshore of Vancouver Island, Canada, to the Fairweather Range of southeast Alaska. An active strike-slip boundary similar to California’s San Andreas fault, the Queen Charlotte Fault has produced five magnitude-7-and-higher earthquakes in the last 100 years (see stars in image A) and presents the greatest earthquake hazard to residents of southeast Alaska and western British Columbia.” (USGS 2022, Image Credit: USGS 2018)

“Four million years ago the Juan de Fuca oceanic plate offshore British Columbia was sheared and began to split off its northern section. This occurred along a shear zone we now call the Nootka fracture zone (NFZ). It generates many small earthquakes in the oceanic rocks, and its extension under Vancouver Island has generated sizable earthquakes felt by residents of the island.” (Rohr et al. 2018)

Image Credit: USGS

Is it possible for a Cascadia megathrust earthquake to travel north all the way to where the fault meets the Queen Charlotte Fault? If so, could Cascadia theoretically trigger an earthquake on the Queen Charlotte Fault in the same way it has occasionally triggered a rupture on the Northern San Andreas Fault to the south?

There is no evidence of the two faults rupturing in near time. This may be because, “it is not known whether megathrust earthquakes can occur along the Explorer segment itself,” (Gao et al. 2017). Geologic records covering the most recent 10,000 years show Cascadia earthquakes most likely ending in the north at about the Nootka Fault, shown on this depiction, dividing the Juan de Fuca from the Explorer Plate. Other experts agree that the “results [of their research] indicate that strong ground shaking is probably not experienced during large subduction earthquakes on the Explorer Plate,” (Riedel et al., 2015). However, uncertainty remains. After all…

Image Credit: (Fossen, 151)

“This is a good question, as it is an unresolved one that researchers are working on. I think there is a consensus developing of “probably not” – meaning the Explorer plate may not really be actively subducting anymore – maybe it’s too small and too buoyant to slide down. It may be in the process of breaking up or being transferred to the Pacific plate side. In that case, the Nootka fault is as far north along the sub zone that we might expect a megathrust quake to go. However, no one is really going to know until it happens.” – Harold Tobin, Director of the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network

(To view the full conversation with the field experts who provided the answers on this page, click here.)

“Agree with Harold…There is also negative evidence north of the Nootka fault in the form of cores collected by the Canadians with minimal turbidite evidence. This is in a report but not very widely known.” – Chris Goldfinger, Oregon State University Professor Emeritus

“The explorer plate has no slow slip or tremor (no ETS), which is probably good evidence against subduction since the rest of Cascadia has these features. I have a student working on using slow slip to characterize the tectonics of the JdF / explorer boundary zone under Vancouver island. We think there may be a sliver between the JdF [Juan de Fuca] and Explorer that is subducting but more slowly, with shear zones on either side of the sliver.

So, I agree the Explorer plate probably isn’t actively subducting. But I would not go as far as to say it couldn’t rupture in a megathrust event, or a rupture couldn’t connect up to the Queen Charlotte fault. Not that I think this is likely to happen, but I do think it’s technically possible. Once a large rupture is propagating, there are dynamic effects that can cause a fault to slip that probably wouldn’t have otherwise. Multi-fault ruptures absolutely do happen, even (especially?) in very large earthquakes. See the Kaikoura earthquake, for example, which may also have ruptured on a subduction interface despite being mainly on shallower faults.” – Noel Jackson, University of Kansas Assistant Professor

Another paper on the topic: Morphology of the Explorer–Juan de Fuca slab edge in northern Cascadia: Imaging plate capture at a ridge-trench-transform triple junction (Audet et al. 2008)