Surviving Cascadia is solely intended to provide information and, therefore, serves a “messenger” role with a focus on full transparency. In Amanda Ripley’s FEMA PrepTalk, The Unthinkable: Lessons from Survivors, she states, “It is regular people; your friends, your family, coworkers, and hotel workers who will be there for you in a disaster. So, our best chance is to trust them more. With more information sooner, more transparency than we’re comfortable with. Then we know we’re doing it right.” I couldn’t agree more.

So, in the spirit of transparency, let’s discuss what to do when ShakeAlert warns that an earthquake is about to start or you feel shaking. It’s a question we’ve all asked. Drop! Cover! Hold On! (DCHO) is the most common, and in many cases, the only message communicated as a protective action. It’s a form of simple messaging, a unified soundbite meant to protect most people in most situations (though if you’ve read Surviving Cascadia’s DCHO page, you’ve seen that even DCHO messaging is complex). But here’s the thing, the DCHO message won’t be the best choice for all people in all situations. It’s more of a triaged approach. This page advocates for expanding the messaging to be more inclusive.

Because the devastating reality is that some Pacific Northwest buildings are at risk of experiencing partial or complete collapse in a major earthquake.

Running out of a building during shaking can be very dangerous, making Drop! Cover! and Hold On! the best option for most people in most situations. However, in the times not covered by “most,” evacuating a building may be the better choice, particularly when ShakeAlert may allow evacuation to occur before the shaking (“go” option). Thankfully, the messaging conversation is expanding in some areas.

Three current Oregon laws allow schools (336.071), state and local agencies (401.900), and private employers (401.902) to practice protective actions other than DCHO in certain buildings.

Mexico, Israel, and Taiwan provide official advice as a split policy that if you are on the ground floor, you should run out of the building and for other floors, practice DCHO.

Where there is hesitation to expand the conversation, I offer the following for consideration.

As stated above, and it bears repeating, there are many buildings in the Pacific Northwest at risk of partial and complete collapse during a Cascadia megathrust earthquake—a reality discussed openly by many expert-level organizations in the field. Here are a few examples available to the general public.

- Oregon Resilience Plan: At the time of publication, roughly 1,000 public school buildings had a rating of high or very high risk of collapse.

- University of Oregon’s All Things Cascadia: “In short, many Pacific Northwest public schools are at risk of falling down on their occupants during a Cascadia megathrust event.”

- State of Oregon Cascadia subduction zone catastrophic earthquake and tsunami operations plan estimated 25,000 injuries as a result of collapsed buildings and states, “Every coastal hospital will either be completely or extensively damaged.”

- Oregon Department of Emergency Management’s (OEM) IronOR ’24 Cascadia functional exercise: Includes the following statements in the exercise scenario, “A significant number of unreinforced masonry, non-ductile concrete, and tilt-up buildings collapsed… Oregon National Guard coordinated the aerial assessments of the affected regions to obtain a comprehensive view of the damage… The assessments identified numerous areas where buildings had collapsed, leading to significant casualties and entrapments.”

- Washington Military Department, Washington State Department of Natural Resources, USGS & FEMA: “Structural collapse (complete damage) of thousands of buildings [in Washington] is also expected (more than 3,000 in Clallam County).”

- Spokesman-Review: “Many of the older buildings in Seattle and elsewhere in Western Washington are not built to withstand the Big One. Buildings made of unreinforced masonry, like many of Spokane’s older brick buildings, or inflexible concrete are particularly susceptible to collapse.”

- Citywide Seismic Vulnerability Assessment of The City of Victoria BC: “Pre-1972 construction including low-rise buildings (concrete, steel, and reinforced masonry), unreinforced masonry (of all heights), and 3-4 story wood apartment buildings; and pre-1960 single family wood homes are at a high seismic risk. Soft soil and vulnerabilities such as cripple walls and sub-floors in single family wood homes, and tuck-under parking in wood apartment buildings make these buildings even more vulnerable to severe levels of ground shaking. Additionally, pre-1972 mid- and high-rise buildings; post 1972 unreinforced masonry; and concrete/steel/masonry low-rise and 3-4 story wood apartment buildings constructed from 1972-1990 on soft soil are also at a high seismic risk.”

- Portland Public Schools District Assessments for seismic stability, conducted by Holmes, (report available here) found 23 (plus a potential addition of 6 others) schools were at risk of collapse. 19 of those schools are elementary or middle school level (listed out here) are listed as top priorities to retrofit in coming years if the 2025 $1.83 billion bond measure passes. The most vulnerable buildings are listed below:

Oregon Governor Kotek’s 2025 Executive Order, Constructing Seismically Resilient State Buildings, states, “a strong earthquake would cause many structures to collapse and create widespread disruption to utility and transportation networks… the earthquake and resulting damage would cause thousands of injuries and deaths…”

When community members are presented with the realities laid out above, yet receive DCHO messaging alone, it’s unclear to those communities why other options are not provided/discussed. This may give the impression that the messenger is either uninformed or worse, not being transparent. Surviving Cascadia, as a messenger, is providing this page an attempt to be more transparent.

It is sometimes argued that messaging options outside of DCHO may be confusing to the public, that community members may not have enough knowledge on the subject to make the right choice between the options when the time comes. Yet, offering less education only increases the chances that the general public receives less education.

Another common argument against offering DCHO is that messaging should be short, simple, and easy to digest. Tic-Toc and other social media platforms serve as evidence that this sort of messaging can be incredibly effective. Powerful, important messaging is disseminated through these venues and can reach millions of people instantly. But for those who are interested, community members also need avenues to a dive deeper. That’s where the opportunity to expand this conversation could also be powerful.

Running out of a building during shaking can be dangerous and even deadly. However, as discussed above, situations exist where evacuation may be the better option—where practicing DCHO may actually be the more dangerous and even deadly option.

Holding back the “go” option, means the messengers themselves have a potentially unfair advantage. They will have that extra tool in the tool belt when the time comes. That extra layer aiding their situational awareness may have them choosing to “go”—the very option they are telling community members not to do. And making that choice to “go” might save the messenger’s life. More, messaging only DCHO to community members means some will die… specifically because they followed the trusted advice of the messenger.

Added to that grim reality is the fact that when the dust settles after their death, their families may learn that DCHO wasn’t the right message for their loved one’s situation during the shaking… and the trust in messengers tasked with keeping communities safe before, during and after disasters could crumble. We, as messengers, owe it to communities to provide them with the same information we hold.

Newer homes are typically more expensive and more likely to be built to current seismic codes. For older homes, seismic retrofits can be expensive, particularly retrofitting beyond basic levels required for “life safety”. Current codes do not require going beyond building to life safety in many cases. In a presentation by the Oregon Seismic Safety Policy Advisory Commission (OSSPAC) titled, Earthquake Resilience: Building Resilient Communities, engineers discuss the “current status of the nation with regard to resilience” and building categories. Note that Category D is the current standard used for most seismic retrofits

- There is no such thing as a fully compliant city

- Code adoption is neither universal nor comprehensive

- Enormous diversity exists in how model codes are adopted and enforced

- Even with full compliance, current codes would not provide resilience.

- Codes are designed to safeguard life and support emergency response

- Codes do not provide for post-disaster performance

- Category A: Safe and Operational

- Essential facilities such as hospitals and emergency operations centers

- Life Line Category I: “Resume essential service in 4 hours”

- Category B: Safe and Usable During Repair

- “Shelter-in-place” residential buildings and buildings needed for emergency operations

- Life Line Category II: “Resume 100% workforce service within 4 months”

- Category C: Safe and Usable After Repair

- Current minimum design standard for new, non-essential buildings

- Life Line Category III: “Resume 100% commercial service within 36 months”

- *Category D: Safe But Not Repairable

- Below standard for new, non-essential buildings. Often used as a performance goal for existing buildings.

- Category E: Unsafe

- Partial or complete collapse: damage that will lead to casualties in the event of the “expected” earthquake – the killer buildings

In other words, the better the retrofit, the safer the building AND the more likely it will be usable in the aftermath of Cascadia—not necessarily a DCHO consideration, but one that impacts life safety after the quake. The fact remains, though, that vulnerable communities are often at the greatest risk of living in buildings that are not designed, even to the “life safety” standard to withstand Cascadia. According to a 2024 study by UCLA that looked at retrofits in the Los Angeles area, “households with lower retrofit rates correlated with disparities in race and ethnicity, as well as with lower income levels”. Messaging DCHO alone leaves out the very option that many in these communities may need to hear most.

To further hammer this home, messaging to protect “most people” leaves out community members who need to be aware of other potential protective actions. While responders often have to triage victims and prioritize resources, messengers aiming to educate well in advance of a disaster aren’t limited by those same restraints. We have the opportunity to go beyond the “most people/most situations” level to incorporate the whole community.

When the next Cascadia megathrust earthquake strikes the Pacific Northwest, the first tsunami wave could reach some Pacific Northwest beaches in as little 10 minutes… That’s 10 minutes from the time the shaking begins, not from the time the shaking ends. Subduction zone earthquakes can last between 3 and 7 minutes.

It’s worth noting that the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries (DOGAMI) conservatively estimates that it takes 7 minutes for people to organize themselves, leave the building, and begin to evacuate. If the shaking “only” lasts 3 minutes, community members spend 7 minutes heading out the door, and they live right near the beach, that first tsunami wave could reach them just as they reach the starting point of the evacuation route. Their situation leaves very little time between the end of the shaking and the arrival of that first wave (especially if the shaking lasts longer than 3 minutes)… and that’s their situation if they are in a seismically safe building.

It’s all the more complicated if they are in a building that is not structurally sound. Shaking will be strong along the coast. As shown in the image below, most cities will experience severe or violent shaking. Some buildings will collapse. There is also the risk of entrapment from heavy furniture that is overturned and blocking exits or doors jamming shut. These potentials greatly increasing the amount of time it takes someone to evacuate. For someone who:

- gets the ShakeAlert message before the shaking starts and

- knows they may have precious few minutes after the shaking ends to reach high ground and

- may be in an unstable building and doesn’t want to risk entrapment… or collapse,

they may choose to evacuate the building before the shaking starts. However, they are much less likely to know that’s something they should consider if the messaging tells them DCHO is the only right answer.

Retrofitting a building (or other infrastructure such as bridges, culverts, dams, etc.) saves lives when done correctly. It saves money too, according to the Natural Hazard Mitigation Saves: 2019 Report – National Institute of Building Sciences. You can pull up their earthquake PDFs for Adopt Life Safety Building Codes, Adopt Building Codes that Exceed Life Safety, Retrofits, and mitigation efforts through Federal Grants for more details.

This video from FEMA’s Residential Seismic Rehabilitation Course P-593 shows that some retrofits, done well, prevent collapse. In this video, the home in the foreground has not been retrofitted, while the home farther back has been. Watch what happens when they shake on the table.

This video is 22 seconds long. A reminder that the next Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake is expected to shake for at least 3 minutes.

However, even some seismically retrofitted URM buildings may not withstand a Cascadia earthquake. In a 2023 Temblor article, a team of experts “worked with practicing structural engineers to design a test structure that would directly mirror today’s real-world retrofits.” They wanted to see how it would hold up during shaking… This 25-second video is eye-opening, showing the dangers of DHCO and evacuation. *Keep in mind, a Cascadia megathrust earthquake is expected to shake anywhere between 3 and 7 minutes.

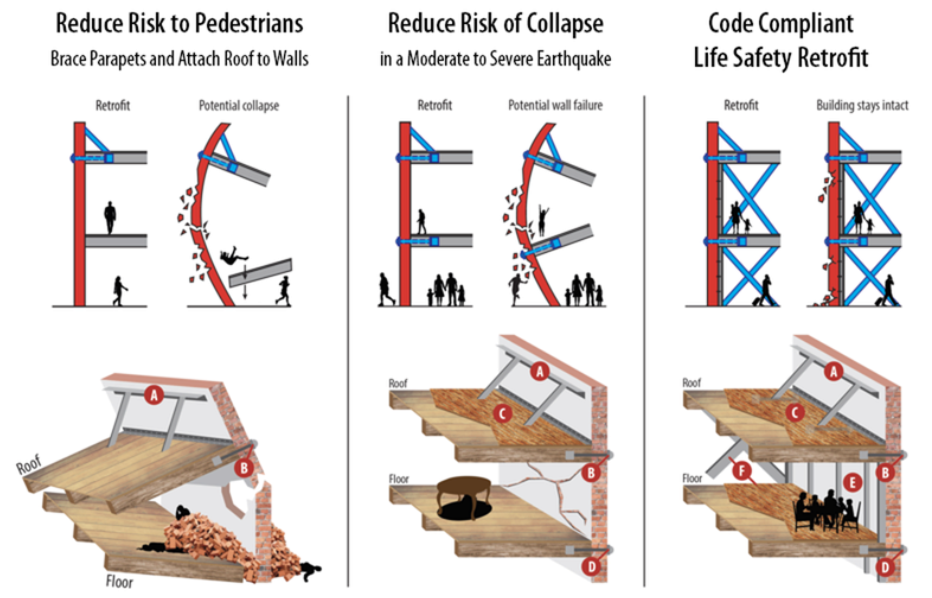

The building in that video was retrofitted to be code compliant for life safety. It’s worth noting that not all seismic retrofits are created equal. This image below, from the City of Portland, shows how some retrofitted buildings may not even meet that standard.

Seattle Emergency Management also has a useful page with GIFs embedded, and they provide the following video in which Nancy Devine, P.E, S.E., Senior Structural Plans Engineer for the Seattle Department of Constructions and Inspections, discusses Identifying Unreinforced Masonry URM Buildings.

Oregon State University Professor Emeritus, Chris Goldfinger is one of the world’s leading experts on subduction zones. He is one of the most vocal advocates for expanding the conversation beyond the simple message. He’s interviewed in this PBS video and offers his opinion in this Temblor article, as well.

It’s worth noting that there is inconsistent research on whether to “Stay or Go”. FEMA’s Earthquake | Evacuation: Exiting an Unreinforced Masonry Building page provides the following two examples. Note that neither event occurred in the US, meaning building materials and building codes may vary from those in the Pacific Northwest.

| Example where it was more dangerous to exit URM buildings during an earthquake due to masonry falling into the streets and sidewalks below: | “Evacuating un-reinforced masonry buildings during the shaking appears to increase the risk of injury by a factor of three.” – Evidence-based Public Education for Disaster Prevention: Causes of Deaths and Injuries in the 1999 Kocaeli Earthquake. |

| Example where it was safer to exit URM buildings during an earthquake: | “The possibility for escape was crucial for survival and depended on the type of building… In the seven villages studied, all the deaths and injuries which occurred within 48 hours of the impact were associated with the collapse of houses.” – World Health Organization, A case-control study of injuries arising from the earthquake in Armenia, 1988. |

This page is not—I repeat— is NOT me telling you which choice is right for you. I’m not making any recommendations. I’m not qualified to do so. Instead, this page is intended to introduce you to the broader conversation so you can soak in both sides, talk with the experts about your particular situation, and make the choice that you think is right for you.