Why minutes matter, and how infrastructure can turn the tide

On January 26, 2026, the Pacific Northwest marks the 326th anniversary of the last great Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake and tsunami of 1700. More than three centuries later, we wait for the next one, knowing it is not a question of if, but when.

When that day comes, the greatest loss of life will almost certainly result from tsunami impacts along the coast. The good news is that this outcome is not inevitable. Strategically placed vertical evacuation structures (VES) can shorten the distance to safety and reduce evacuation time for community members—and their pets—directly saving lives when every minute counts.

January 26th is not about fear. It is about responsibility. The last Cascadia earthquake gave no warning, and the next will be no different. But unlike in 1700, we now have the data, the engineering, and the opportunity to act. What remains is the choice to do so.

This week offers a timely opportunity for coastal communities, decision-makers, and the public to focus on one of the most effective tools available for reducing tsunami risk: vertical evacuation structures. In regions where natural high ground is too far to reach in time, VES provide a practical, proven way to shorten evacuation distances and turn minutes into survivable outcomes. Oregon’s coast illustrates both the urgency of the problem and the potential of this solution.

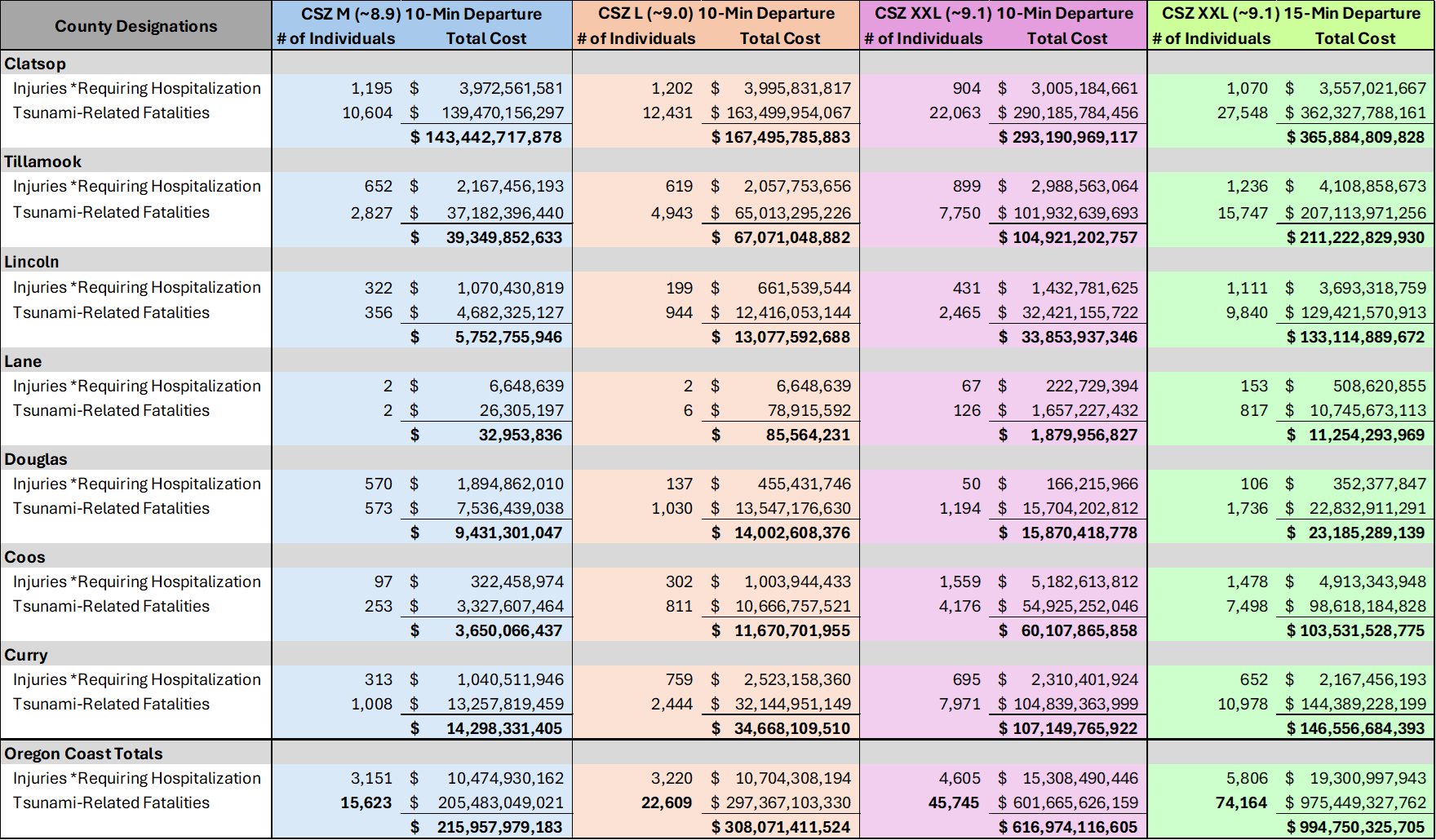

The Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries’ Open-File Report O-25-01, Earthquake and Tsunami Impact Analysis for the Oregon Coast, offers the most current estimates of injuries and fatalities from a Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake and tsunami, summarized in Table 1 below.

These estimates are based on a nighttime (2:00 a.m.) scenario, when people are most likely to be at home, in hotels, vacation rentals, or campgrounds. Lodging facilities are assumed to be fully occupied, reflecting peak vulnerability. Importantly, the analysis does not include day trippers, who account for roughly 4.9% of visitors to the Oregon Coast—meaning the true exposure may be even higher.

DOGAMI’s modeling shows that with a 10-minute departure time, combined resident and visitor fatalities range from approximately 15,550 in an M1 scenario to 45,700 in an XXL1 scenario. With an average 15-minute departure time, fatalities in an XXL scenario soar to an estimated 74,164 people. The good news is that these numbers are not fixed outcomes. They represent tens of thousands of lives that could potentially be saved through proactive investment in vertical evacuation structures along Pacific Northwest coastlines.

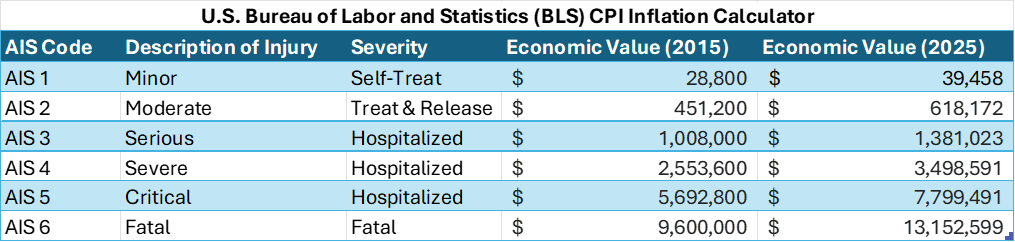

Cost is often cited as the primary barrier to building tsunami vertical evacuation structures. But the financial case for saving lives is far stronger than many realize. Table 1 incorporates Values of a Statistical Life (VSL) from Table 2—metrics commonly used in benefit-cost analyses for infrastructure projects like tsunami evacuation towers. When viewed through this lens, the economic benefits of avoided fatalities alone are staggering, far exceeding the cost of construction. And even that accounting falls short of the true value of lives saved.

Table 1

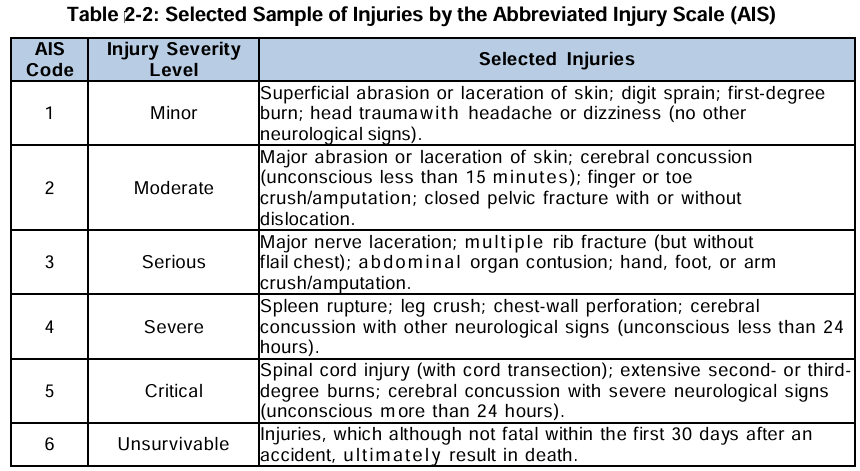

At present, Hazus does not estimate the severity of tsunami-related injuries. However, evidence from the Cascadia CoPes Hub and the National Risk Index makes one reality clear: anyone caught in approximately two meters (about 6.5 feet) of tsunami water has only a 1 percent chance of survival. At lower depths, survival odds may approach 50 percent—but survival does not mean escaping without serious harm.

Tsunamis are not gentle floods. They are fast-moving, highly destructive flows filled with debris—cars, lumber, glass, boats, and fragments of buildings. People swept up in a tsunami are far more likely to suffer severe, life-threatening injuries than minor ones. These injuries would occur in a post-earthquake environment where communities are isolated, power, water, and sanitation systems are disrupted, and coastal hospitals may be damaged, destroyed, or operating with severely limited capacity. In this context, every serious injury avoided matters.

The cost estimates presented in Table 1 draw from the values summarized in Table 2.

For communities considering vertical evacuation structures, both FEMA and the State of Washington currently provide guidance documents to support planning, design, and implementation processes. The State of Oregon has also developed draft guidance, now under review and expected to be published in spring 2026.

- FEMA Guidelines for Design of Structures for Vertical Evacuation from Tsunamis

- First Edition, FEMA P646 / June 2008

- Second Edition, FEMA P-646 / April 2012

- Third Edition, FEMA P-646 / August 2019

- FEMA Vertical Evacuation from Tsunamis: A Guide for Community Officials

- Washington’s Manual for Tsunami Vertical Evacuation Structures

- First Edition, November 2018

- Second Edition, October 2024

- Additional information on vertical evacuation structures is available through the Washington Emergency Management Division’s website.

Hospitalization costs used in Table 1 reflect the average economic value, in 2025 dollars, for injuries classified as AIS 2 through AIS 5, estimated at $3,324,319 per individual.

Table 2

In referrence to Table 2 abbreviated injury scale levels listed above:

Leave a comment