On New Year’s Eve, FEMA’s acting chief, Karen Evans, instructed that roughly 50 of the agency’s Cadre of On-Call Response and Recovery (CORE) teams would not have their contracts renewed—letting them go just days before they were scheduled to finish their assignments.

FEMA currently employs over 8,000 CORE staff—about 40% of its workforce—who are typically hired on 2- or 4-year contracts that have historically been renewed. In 2025, however, new CORE hires were given only 180-day contracts, and a CNN article first reported that several thousand more will see their contracts end in 2026, with renewal now uncertain.

These personell are critical to efforts that could help communities prepare for, mitigate against, respond to, and recover from a major Cascadia subduction zone earthquake and tsunami. Without them, your community will likely face slower evacuations and family reunifications, delayed aid, and longer recovery.

Emergency management employees are not typically the ones handing out water, food, or setting up shelters for disaster survivors. Instead, think of disaster response like a chessboard. The water, food, shelter, medical care, and other services are the chess pieces. Emergency management agencies aren’t the pieces themselves—they are the hands that strategically place those pieces on the board.

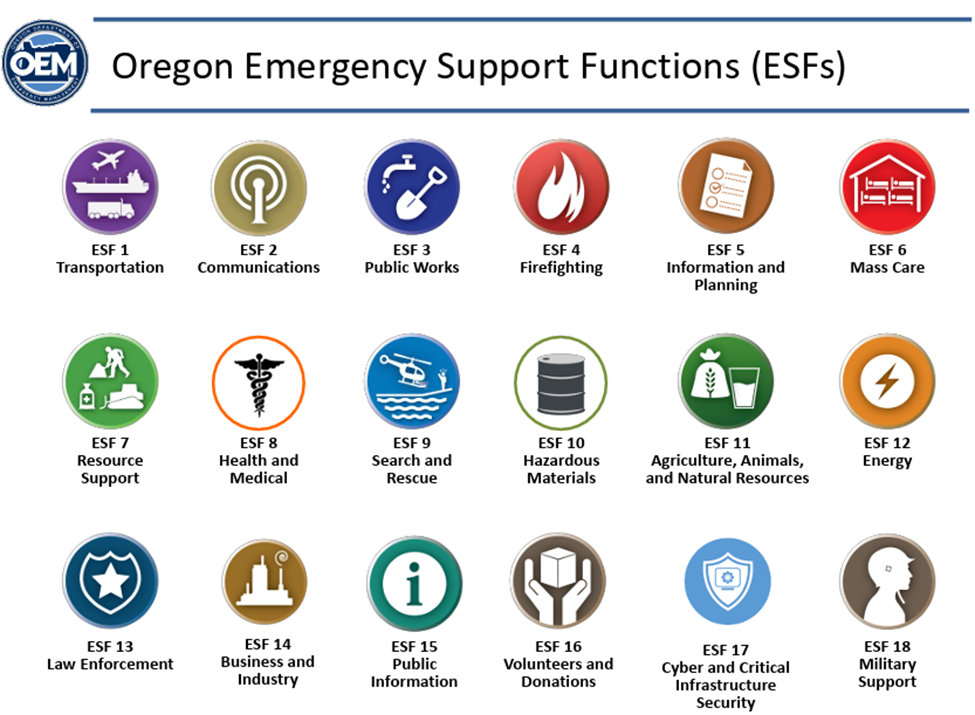

Their role is to identify needs, set priorities, and coordinate the response by bringing together the right partners at the right time. These partners are organized into groups known as Emergency Support Functions (ESFs), which include agencies and organizations responsible for things like transportation, communications, mass care, public health, and infrastructure.

For example, after a Cascadia earthquake and tsunami, emergency management professionals may identify that coastal communities need shelter, food and water for displaced residents. Rather than providing those services themselves, they activate ESF #6 (Mass Care, Emergency Assistance, Housing, and Human Services). This brings together organizations such as the Red Cross, local governments, faith-based groups, and state agencies to open shelters, provide meals, and support displaced survivors—while emergency management continues coordinating the overall response.

Emergency management is organized in layers, so disasters are handled as close to home as possible — while still allowing help to scale up for major events like a Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake and tsunami.

Local Level (City, County, Tribe)

Local jurisdictions are the first line of response. If an event overwhelms their resources or capacity, they can request assistance from neighboring jurisdictions or higher levels of government.

Mutual Aid (level 1)

When local resources are insufficient, neighboring jurisdictions help each other through mutual aid agreements, such as county-to-county assistance.

State Level

If local and mutual aid capabilities are overwhelmed, the state steps in to coordinate a larger response. Key agencies in the Pacific Northwest include:

- California Office of Emergency Services (Cal OES)

- Oregon Department of Emergency Management (OEM)

- Washington Emergency Management Division (Washington EMD)

The better funded these agencies are, the stronger their capabilities—and the faster their response will be when disaster strikes.

Mutual Aid (level 2)

Neighbors helping neighbors at a larger scale. States can coordinate regional and interstate mutual aid to maximize resources across boundaries.

Federal Level (FEMA)

Before a state can request federal assistance, it must show that the disaster exceeds its capacity to respond. This involves:

- Assessing damage to homes, infrastructure, and lives

- Identifying resource shortfalls, such as personnel, equipment, or funding

- Demonstrating that the costs of response and recovery exceed what the state can reasonably cover

Only after meeting these criteria can FEMA provide support. Even then, federal assistance does not arrive immediately. In a Cascadia scenario, meaningful federal support may take days to weeks, not hours.

International Assistance

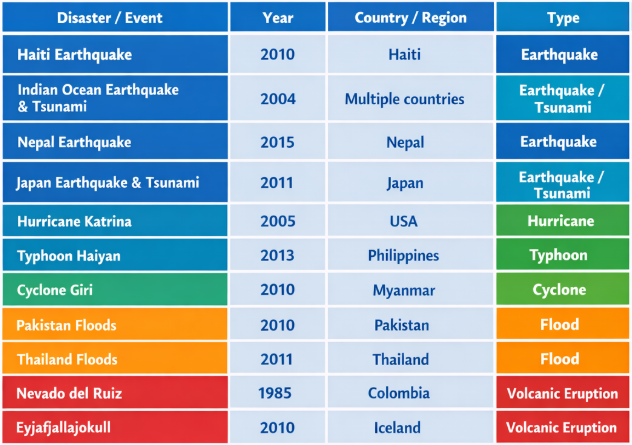

Some disasters exceed even national capacities and require international support. Examples of such events are shown below.

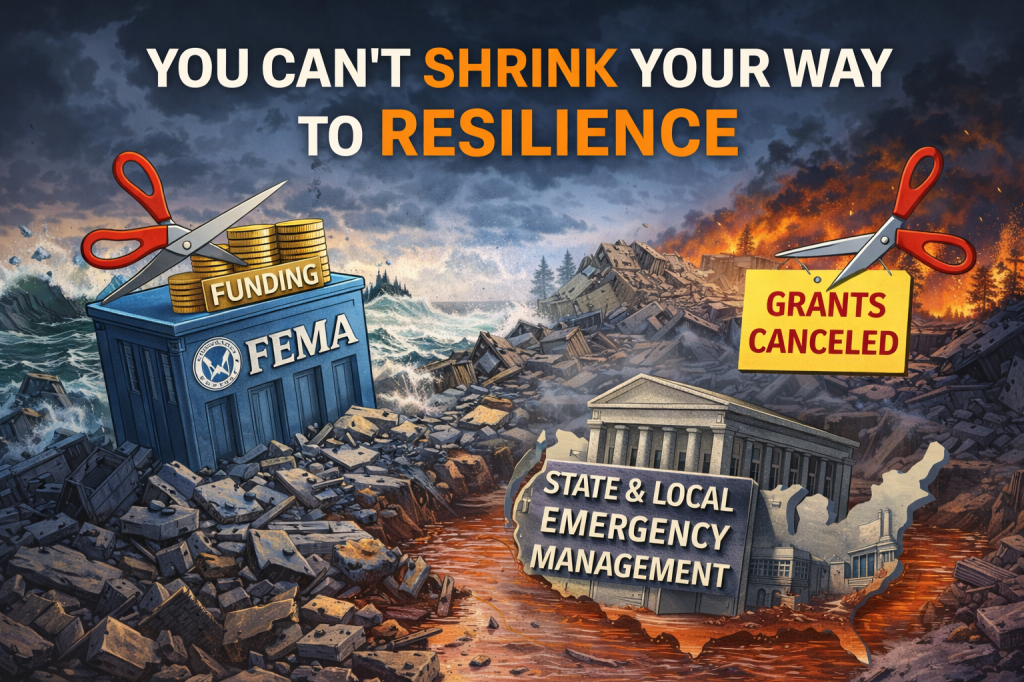

Funding and staffing cuts at FEMA are often framed as “returning power to the states,” implying that FEMA has somehow prevented states from managing disasters on their own. That framing is misleading.

FEMA does not self-deploy. It only becomes involved when a state formally requests assistance—and only after the state demonstrates that the disaster exceeds its own capacity and resources. In other words, FEMA’s involvement is not a takeover. It is a backstop, activated when state and local systems are overwhelmed.

State and local emergency management agencies rely in part on state and local taxes, but in practice, those revenues are far insufficient to meet real preparedness and response needs—a reality across much of the country.

In theory, if the federal government increased funding to states, while also maintaining robust federal staffing, states could strengthen their programs—hiring more personnel, improving planning, and building stronger interstate mutual aid agreements. With enough support, states would be better positioned to manage many disasters on their own.

But the reality in 2025 was the opposite. Federal grants to states were cut, and staffing at FEMA was reduced, undermining both state and national capacity. Even well-funded states cannot fully compensate for these losses, and catastrophic events like a Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake and tsunami would still require a coordinated national—and likely international—response. Instead of strengthening the system, these cuts have weakened it at every level.

Take Oregon as an example. The state’s tax base does not generate enough revenue to adequately fund emergency management at the state or local level. More than 80% of funding for the Oregon Department of Emergency Management (OEM) comes from federal grants, many of which have already been reduced or now face uncertain futures. As reported by CNN:

“With the future of federal funding up in the air, some states are already tightening their own budgets and laying off local emergency management staff whose departments rely on money from FEMA to brace for the impact.”

To replace lost federal funding, states and local governments are left with two options:

- Raise taxes, or

- Divert funding from other critical services

Neither option strengthens preparedness. Both create new vulnerabilities.

FEMA was created in 1979 precisely because disasters routinely overwhelmed state and local governments. It was further strengthened after Hurricane Katrina revealed just how much coordination, staffing, and logistics are required for truly catastrophic events.

FEMA is not perfect. But if an agency is already operating well below needed capacity—as FEMA reportedly was entering 2025—cutting staff and funding will not improve outcomes. No emergency management system performs better when it is under-resourced.

If the goal is resilience, preparedness, and faster recovery, the solution is not to weaken FEMA. It is to adequately staff it, fund it, and improve its processes—while continuing to invest in state and local partners.

For a Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake and tsunami, emergency management capability is not an abstract policy issue—it is the difference between coordination and chaos. It is the difference between life and death.

Cascadia will affect multiple states at once, damage ports, highways, hospitals, and communications systems, and isolate coastal and rural communities for weeks or longer.

No state, and no collection of states, can manage an event of this scale without a fully staffed, well-funded federal partner ready to coordinate logistics, move resources across the country, and sustain response and recovery over months and years. Weakening that capability before the ground starts shaking does not make the system more resilient—it guarantees longer delays, deeper suffering, and a slower recovery when Cascadia inevitably occurs.

Leave a comment